Interview with a Researcher

By Dez Alaniz, Director of the Presidio Research Center Here at SBTHP’s Presidio Research Center (PRC) we welcome hundreds of scholars, researchers and students each year. This week, I had the privilege of sitting down and interviewing Dr. Amy Andrea Martinez, a visiting scholar who has been spending time with our PRC collections over the past few weeks.

Dra. Amy Andrea Martinez earned her master’s and doctoral degree in Criminal Justice from the Criminal Justice Studies Department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York. Her bachelor’s degree is in Sociology with an emphasis in Crime, Law, and Deviance from Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. As a first-generation, working-class, and system impacted Xicana Indigena from Southern California, her experiences inform her commitment to decolonial gang research on Mexican/Chicano/a families and their associations and experiences with gang and street life.

What is the scope of your research?

Dr. Amy Andrea Martinez

My research is centered on understanding the intersections of Mexican/Chicano gang culture, policing, and carcerality in Santa Barbara, with an emphasis on how these systems perpetuate colonial violence against marginalized communities. [Editor’s note: Carcerality refers to refers to social systems where punishment and incarceration are a primary means of social control].

My work critically examines how these structures are not just a modern-day manifestation of systemic oppression but are deeply embedded in the settler colonial history of Santa Barbara, a city built on stolen Chumash land.

How did your research journey lead you to the Presidio Research Center?

My journey to the Presidio Research Center (PRC) in Santa Barbara has been deeply transformative. I ended up at the PRC because I wanted to understand the colonial underpinnings of both the physical and social infrastructure of the city, and how this history shapes and influences the contemporary policing of those deemed “undesirable”—which, in my view, are Mexican/Chicano/as in the city today. Sifting through primary resources and accounts—many of which are original documents—has been incredibly eye-opening. As a first-generation detribalized Xicana Indígena, there’s something profoundly impactful about physically touching these materials and encountering the raw, unfiltered accounts of Santa Barbara’s history. It’s been a journey of confronting the underlying logics behind the creation of this place, particularly as it relates to the violent development of Santa Barbara and its role in the displacement and (attempted) erasure of Indigenous people, like the Chumash.

What collections or materials have stood out?

What blows my mind is how little attention has been given to the intersections of coloniality, carcerality, and settler colonialism in understanding the racial governance of this city—especially as it pertains to the so-called “gang problem” and how it’s historically been dealt with. There’s an eerie resonance between how the Spanish and Mexican soldiers handled Native Chumash and Indigenous communities during the formal Colonial period, and how the city has historically responded to marginalized populations today. This continuity of colonial violence, embedded in the very infrastructure of the city, remains a crucial piece that I feel is often overlooked.

The collections at the PRC have provided critical insights that have shifted and deepened my understanding of the city’s history. These primary accounts have illuminated the colonial foundations of the systems I study, offering a deeper context for understanding how racial hierarchies were constructed and maintained over time. As I examine these documents, I can trace the historical continuities that have shaped policing practices and gang dynamics in Santa Barbara today.

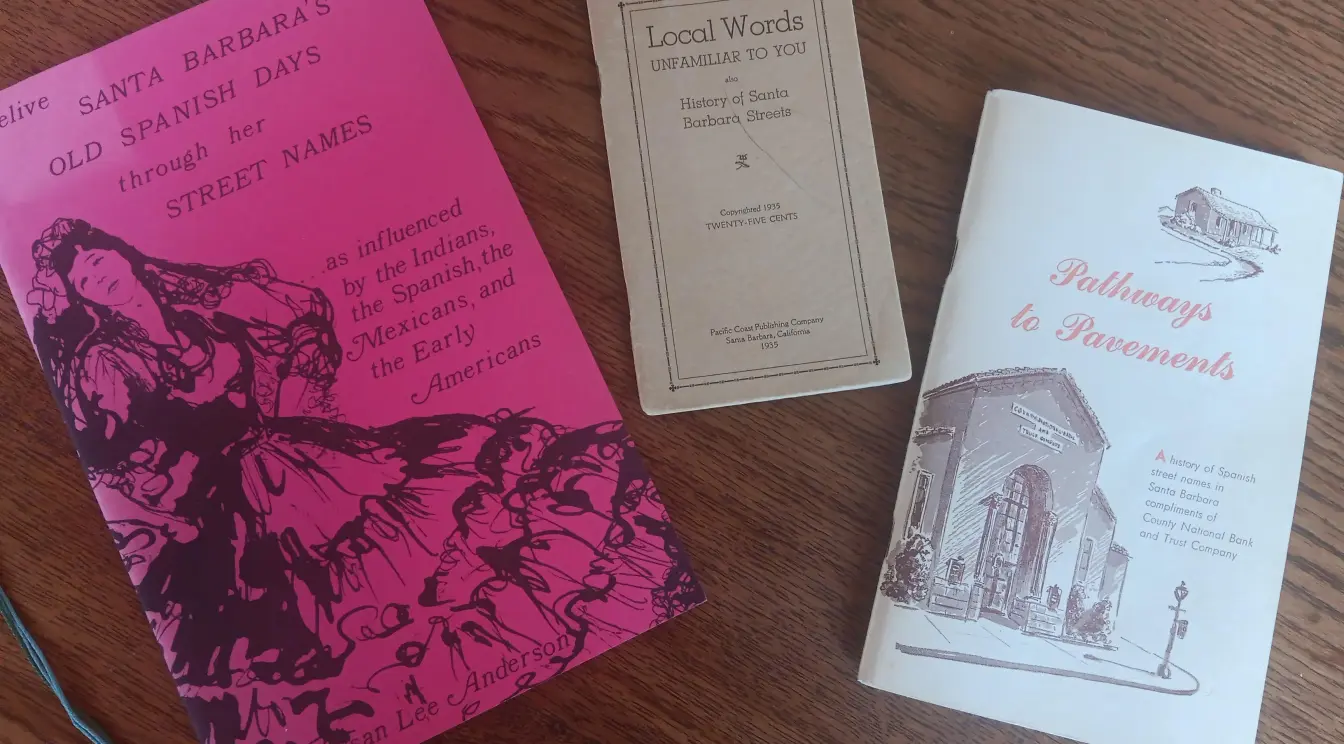

Three items from the Santa Barbara Ephemera Collection. Ephemera, which refers to materials intended to exist or be used for a short time, and materials in this collection include restaurant menus, guidebooks, maps, pamphlets and leaflets, fliers and programs from local events, and other miscellaneous, sometimes tiny items. Dra. Martinez selected several items to review, shown here, to analyze patterns of street naming in Santa Barbara. Photo by Dez Alaniz.

Has anything challenged or surprised you in your research process?

What has been most challenging, yet revealing, in my research process is grappling with the immense power of these historical structures, and how they continue to shape the lived experiences of Mexican/Chicano/a and Chumash communities today. The direct engagement with these materials—seeing firsthand how these logics were built into the very fabric of Santa Barbara—has reinforced the importance of examining the historical roots of modern-day systems of control and has deepened my commitment to understanding and critiquing these systems from a decolonial perspective. I truly feel a particular and personal responsibility to bring to light these hidden histories of the formation and development of this city in a way that is accessible to my community. Moreover, I want the young gang affiliated people I work with to know their history. As Cesar Chavez once said, “You cannot un-educate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.”

To me, Chavez’s words are a powerful reminder that knowledge and awareness are not merely intellectual pursuits—they are acts of resistance. Once someone understands their own history and power, they can no longer be easily controlled or marginalized. This is why it is essential for the young people I work with to learn about their histories, their cultural legacies, and how colonial violence has shaped their present. When people take pride in who they are and understand the systems that have sought to oppress them, they are no longer willing to accept subjugation. They can’t be humiliated, and they can’t be kept down. Education, in this sense, becomes a tool for liberation—one that challenges the status quo. Even if we can’t outright dismantle the systems of control that have been in place for generations, we can strategize and move more intentionally.

I believe one of the most meaningful roles I can play as an educator and storyteller is to harness the power of knowledge production by centering the voices and experiences of the most oppressed. In doing so, I aim to show that the oppressed have never been passive recipients of colonial violence, but active agents in resisting and shaping their own narratives. Finally, it is critically important for me to serve as a vessel for producing critical, revisionist histories that do not perpetuate harm or epistemic violence.

These three titles are from our reference materials, which include primarily scholarly and professional works on a variety of topics related to Presidio and regional history. The Presidio Research Center collections contain a variety of materials that document the histories of different communities in the Presidio neighborhood, including the role of the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation in acquiring the physical space where El Presidio de Santa Barbara was rebuilt. Photo by Dez Alaniz.

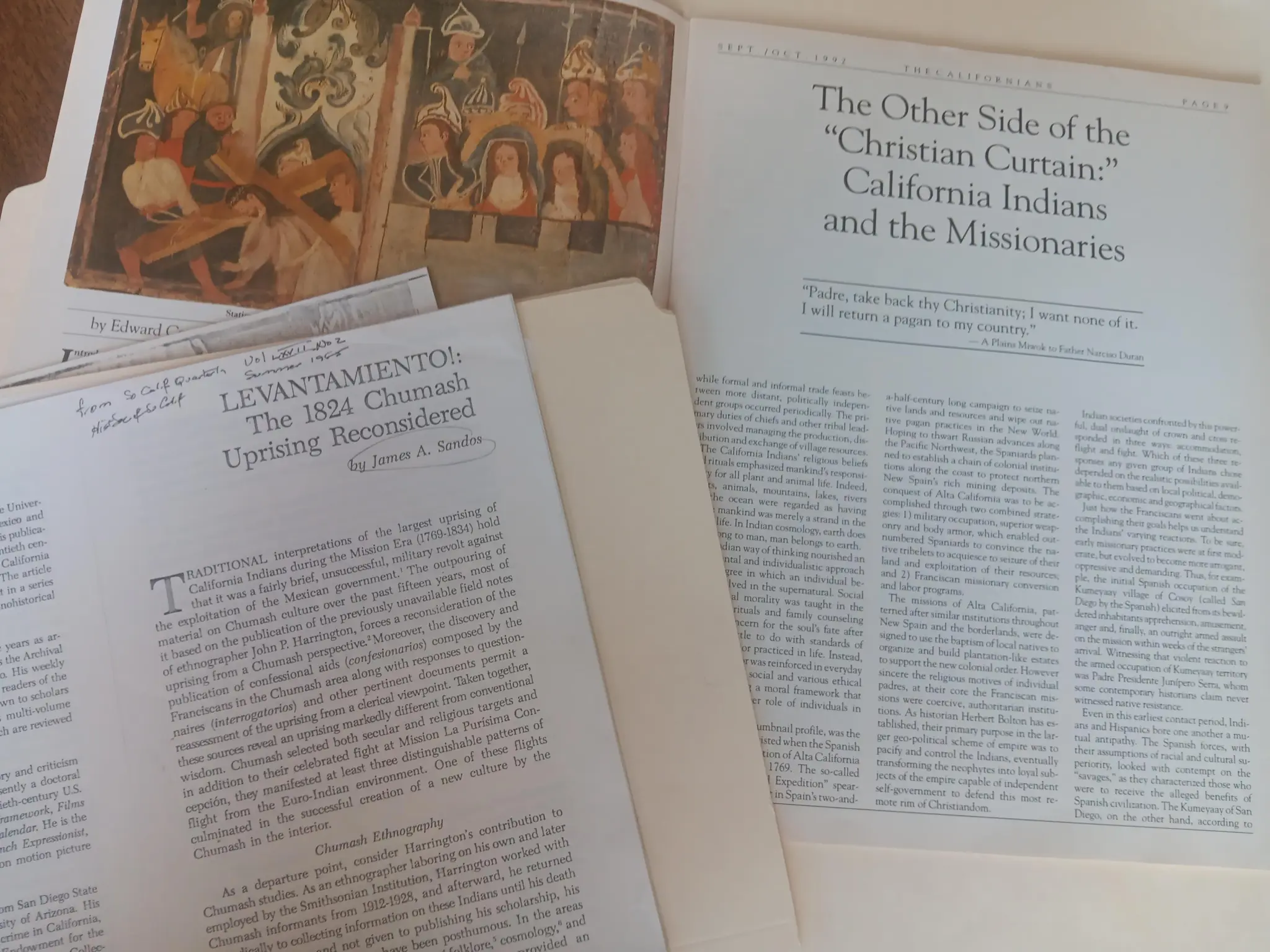

Two articles about the experiences and resistance of Indigenous communities forced to live in the Mission system. These articles are from our Vertical File (VF) collections, which include unpublished manuscripts, government reports, and other material types that don’t fit with other collections. Photo by Dez Alaniz.

Search our Presidio Research Center Catalog.

To make an appointment to visit the Presidio Research Center, email dez@sbthp.org or call (805) 965-0093.